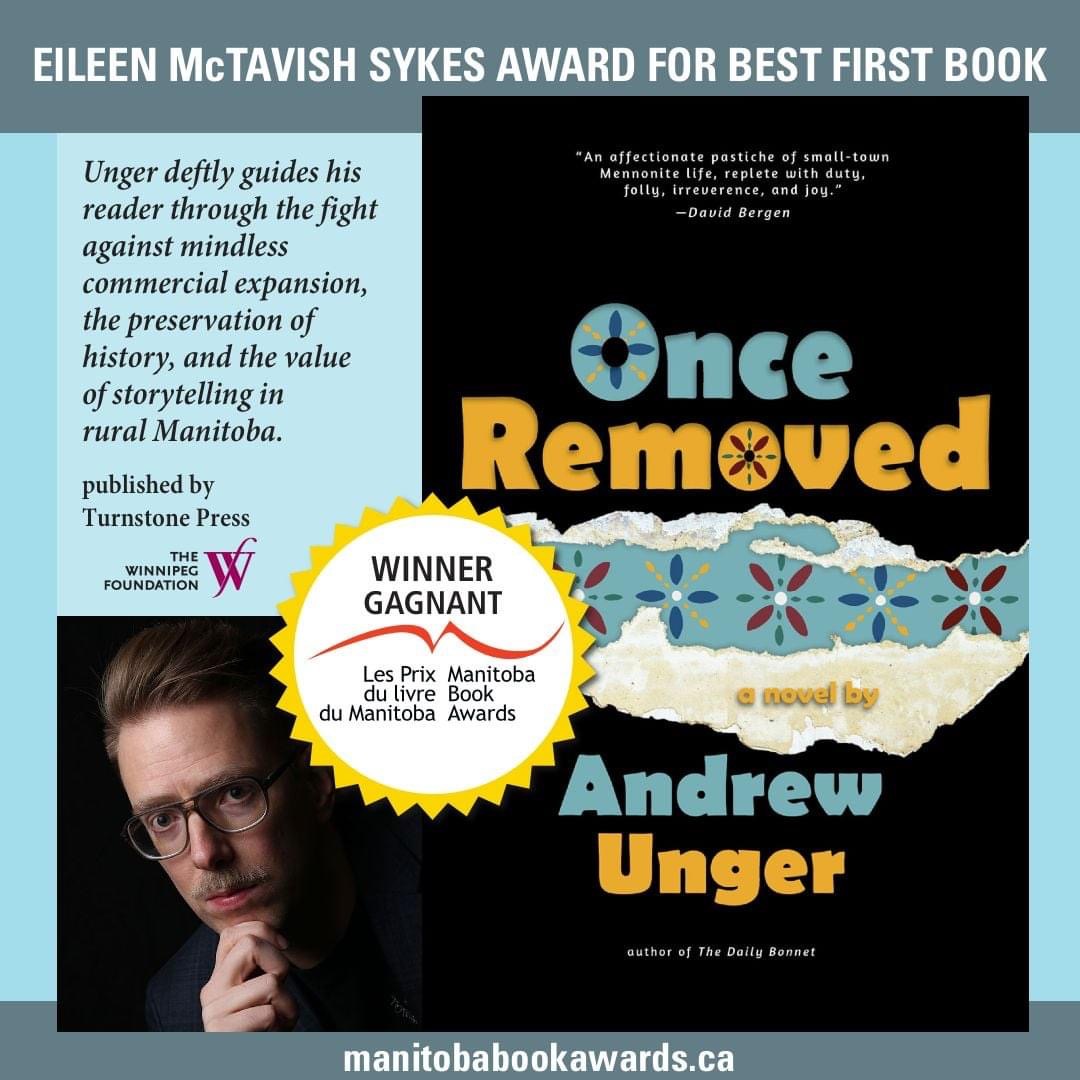

This week, we are excited to present a guest blog post by ghostwriter Andrew Unger. Andrew is uniquely qualified to write about ghostwriting after writing a novel, Once Removed, about a ghostwriter.

You can purchase Andrew’s book here.

And you can visit his satirical website here.

Write What You Know: The Writing Cliché that Is No Lie

“I’m a ghostwriter—or trying to be, anyway. This means I write books for other people. So does Randall. We’re guns for hire, so to speak, though around here gun analogies are generally frowned upon.” – Timothy Heppner in Andrew Unger’s Once Removed (2020, Turnstone Press)

It is perhaps the most widely spread and clichéd piece of advice given to fledgling writers: write what you know. When I began seriously writing about twenty years ago, I had heard this advice, of course, but I never believed it, not really. I felt that my experiences—the things I knew—would be of no interest to others. I lived in a small town on the Canadian prairies and belonged to a fringe religious sect: the Mennonites. Surely, no one would be interested in reading my stories. So, instead, I wrote stories that I felt would appeal to a wider audience. As a Canadian, I set my stories in the United States. I lived in a small town, but I placed my protagonists in large cities. I gave my heroes generic Anglified names. Instead of drawing on specific details from my own life, I went for some misguided notion of the universal, and in doing so my stories were not universal at all. They fell flat.

It took me some time to learn my lesson. In 2016, I started a satire website called the Daily Bonnet, which has been described as a kind of Mennonite version of the Onion. Upon discovering the website, I often hear people say, “I didn’t know the Mennonites had their own satire website.” Some people are shocked we even have a sense of humor. A quick Google search will tell you that Mennonites are a Protestant denomination known for adult baptism, pacifism, and being burned at the stake. If you glance over at the image page, you’ll see men in long beards and women in long black dresses, horse and buggies, butter churning—not all that different from the Amish. In reality, Mennonites are as diverse as the general population. It just so happens that the sort of Mennonites who get blogged about and tagged as “Mennonite” tend to be of the plain dress variety. The sort of Mennonites who shop at the Gap and drive Volvos never make it onto the Google Images page.

Mennonites are niche; I don’t think anyone would consciously set out to create a Mennonite satire website. The Daily Bonnet was an accident, really. I was frustrated with something about my local town council and wrote a satirical article about it on my blog. It was intended as a one-off for a very small audience. Normally a few dozen people would read my writing—usually less than 100—but when I woke up the next morning, I found the article had thousands of views. After that early success, I figured, “Hey, people seem to like this. I could write more of these.” There was an appetite, it seemed, for Mennonite satire and so I started the website a few weeks later. Since then, I’ve written at least one article every day for more than four years—about 2,000 articles by now. I will admit that sometimes the subject matter is rather specialized, but I’ve heard from many people from other cultural or religious groups who tell me they can relate to the humor. The website critiques and pokes fun at traditional Mennonite notions of frugality, piety, gender roles, and so on. These are topics to which many people outside my own tradition can relate. The website attracts millions of visitors each year, has been mentioned in the New Yorker, and read in the Canadian House of Commons. In my attempts to be specific, it seems, I discovered universality, at least of a sort.

Writing the Daily Bonnet taught me to “write what you know,” so when I set out to write a novel, I had a much clearer sense of what I wanted to do. In Once Removed I drew very purposefully on my own culture and experiences. Once Removed tells the story of Timothy Heppner, a ghostwriter struggling to make a living in a small town on the Canadian prairies. It’s fiction, of course, but years ago, I did, in fact, complete a number of ghostwriting projects for Kevin Anderson & Associates. Although in recent years I’ve focused more on my own writing, I have pleasant memories of those experiences and, in some way, ghostwriting has found its way into my novel. Writing a novel about a ghostwriter is uncommon in itself, but a Mennonite ghostwriter? Again, in theory, the story seems rather niche, but I think that’s the appeal. The strangeness of it. In one scene, the image-conscious Edenfeld mayor tasks the town librarians with photographing locals consuming adult beverages and wearing cut-off jean shorts so he can post them online and reshape the town’s image. Timothy’s first elderly ghostwriting client innocently informs him that she’s “heard something about climaxes.”

In trying to capture the specificities of my own culture, I even went so far as to insert Plautdietsch (the Low German dialect spoken by my ancestors) words into the text. A younger version of myself might have been nervous about the inclusion of this vocabulary. However, fellow Mennonite writer Armin Wiebe recently told me that only other Mennonites ask him about the presence of so many Plautdietsch words in his books. “How do people understand the Low German?” they say. No non-Mennonite ever asks him about it. People who read books, Wiebe says, are used to coming across new words. They either skip them or understand them from context. Specificity, Wiebe says, is nothing to be afraid of.

So, yes, believe it when they tell you, “write what you know.” Whether you’re writing an autobiography or science fiction, the story needs to be grounded in human experiences—in your own experiences and observations. People will relate. Anyone who’s traveled will tell you that our cultures and experiences are not nearly as unique and exotic as we might think. A story, well written, will draw readers in and it really matters nuscht how many vedaume Low German words are included.

Bio: Andrew Unger is a writer and educator from Manitoba, Canada, best known as the author of the satire website the Daily Bonnet. His novel Once Removed (2020, Turnstone Press) is available now.

https://www.winnipegfreepress.com/arts-and-life/entertainment/books/bergen-wins-book-of-the-year-a-fourth-time-574461102.html

Categories:

Writing Help